[ad_1]

The plight of British-Iranian woman Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who has been released after being held on spying charges in Iran for almost six years, focused attention on Iranians with dual nationality or foreign permanent residency who are held in the Islamic Republic’s prisons.

Iran does not recognise dual nationality, and there are no exact figures on the number of such detainees given the sensitive nature of the information. Some of the most prominent are:

Morad Tahbaz (Iran-UK-US)

Morad Tahbaz and fellow conservationists were using cameras to track endangered species when they were arrested

The 66-year-old businessman and wildlife conservationist, who also holds American and British citizenship, was arrested during a crackdown on environmental activists in January 2018. His Canadian-Iranian colleague, Kavous Seyed-Emami, died in custody a few weeks later in unexplained circumstances.

The authorities accused Tahbaz and seven other conservationists of collecting classified information about Iran’s strategic areas under the pretext of carrying out environmental and scientific projects.

The conservationists – members of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation – had been using cameras to track endangered species including the Asiatic cheetah and Persian leopard, according to Amnesty International.

UN human rights experts said it was “hard to fathom how working to preserve the Iranian flora and fauna can possibly be linked to conducting espionage against Iranian interests”, while a government committee concluded that there was no evidence to suggest they were spies.

But in October 2018, Tahbaz and three of his fellow conservationists were charged with “corruption on earth” (later changed to “co-operating with the hostile state of the US”), which carries the death penalty. Three others were charged with espionage, and a fourth was accused of acting against national security.

All eight denied the charges and Amnesty International said there was evidence that they had been subjected to torture in order to extract forced “confessions”.

In November 2019, they were sentenced to prison terms ranging from four to 10 years and ordered to return allegedly “illicit income”.

Human Rights Watch denounced what it said was an unfair trial, during which the defendants were apparently unable to see the full dossier of evidence against them.

The Court of Appeals reportedly upheld Tahbaz’s convictions in February 2020.

UN human rights experts warned last year that Tahbaz’s health condition had continuously deteriorated during his imprisonment. Despite that, they added, he had been denied access to proper treatment.

In March 2022, UK Foreign Secretary Liz Truss said Tahbaz had been released from prison on furlough. The announcement came on the same day that Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and fellow British national Anoosheh Ashoori were released by Iran and allowed to return to the UK.

“We will continue to work to secure Morad’s departure from Iran,” Ms Truss said.

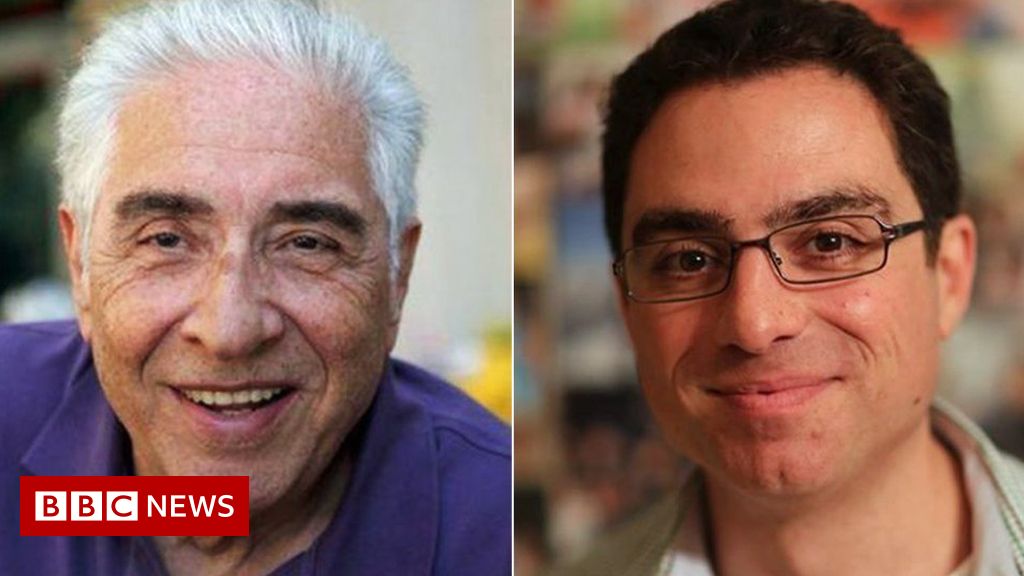

Siamak and Baquer Namazi (Iran-US)

Baquer Namazi (left) and his son Siamak (right) have been detained since 2016 and 2015 respectively

Siamak Namazi, 50, worked as head of strategic planning at Dubai-based Crescent Petroleum.

He was arrested by the Revolutionary Guards in October 2015, while his octogenarian father Baquer, 85, was arrested in February 2016 after Iranian officials granted him permission to visit his son in prison.

That October, they were both sentenced to 10 years in prison by a Revolutionary Court for “co-operating with a foreign enemy state”. An appeals court upheld their sentence in August 2017.

Their lawyer said they denied the charges against them. He also complained that they had been held in solitary confinement and denied access to legal representation, and had suffered health problems. Siamak is also alleged to have been tortured.

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention said the Namazis’ imprisonment violated the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and demanded their release.

Baquer was given medical leave from prison in 2018 and placed under house arrest. However, his health has continued to deteriorate at home.

In early 2020, Baquer was informed that the Revolutionary Court had commuted his sentence to time served and that the bail he had posted for his medical leave was released, according to his lawyer.

Despite the ruling, he was forced to stay in Iran because of an international travel ban, even after he had to undergo surgery to clear near-total arterial blockages in his brain in late 2021.

Siamak remains in Evin prison, along with two other detained US dual nationals.

Ahmadreza Djalali (Iran-Sweden)

Ahmadreza Djalali was sentenced to death in October 2017

The 50-year-old specialist in emergency medicine was arrested in April 2016 while on a business trip from Sweden.

Amnesty International said Djalali was held at Evin prison by intelligence ministry officials for seven months, three of them in solitary confinement, before he was given access to a lawyer.

He alleged that he was subjected to torture and other ill-treatment during that period, including threats to kill or otherwise harm his children, who live in Sweden, and his mother, who lives in Iran.

In October 2017, a Revolutionary Court in Tehran convicted Djalali of “spreading corruption on earth” and sentenced him to death. His lawyers said the court relied primarily on evidence obtained under duress and alleged that he was prosecuted solely because of his refusal to use his academic ties in European institutions to spy for Iran.

Two months later, Iranian state television also aired what it said was footage of Djalali confessing that he had spied on Iran’s nuclear programme for Israel. It suggested he was responsible for identifying two Iranian nuclear scientists who were killed in bomb attacks in 2010.

In November 2020, Iran dismissed an appeal by Sweden’s foreign minister for it to not enforce the death sentence, after Djalali’s wife said he had been informed by prison authorities that faced imminent execution. He spent five months in solitary confinement, awaiting execution, until April 2021, when he reportedly was transferred to a multi-occupancy cell.

Djalali’s family says he has been denied access to appropriate medical care for numerous health complications while in prison.

Sweden gave him citizenship in 2018. He had previously been a permanent resident.

Fariba Adelkhah (Iran-France)

Fariba Adelkhah’s research focused on political and social anthropology

The researcher at Sciences-Po university in Paris is a specialist in social anthropology and the political anthropology of post-revolutionary Iran, and has written a number of books.

At the time of her arrest in Tehran in June 2019, she was examining the movement of Shia clerics between Afghanistan, Iran, and Iraq, and had spent time in the holy city of Qom.

Adelkhah was accused of espionage and other security-related offences.

She protested her innocence and after going on hunger strike, she was admitted to hospital for treatment for severe kidney damage.

Prosecutors dropped the espionage charge before her trial began at the Revolutionary Court in April 2020. The following month, the court sentenced Adelkhah to five years in prison for conspiring against national security and an additional year for propaganda against the establishment.

French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian condemned the sentence and demanded her release.

In October 2020, due to what Sciences-Po called her “health circumstances”, Adelkhah was released on bail and allowed to return to her home in Tehran.

However, Iran’s judiciary announced in January 2022 that it had returned Adelkhah to prison, accusing her of “knowingly violating the limits of house arrest dozens of times”.

French President Emmanuel Macron called the decision “entirely arbitrary” and said all of France was “mobilised for her release”.

Abdolrasoul Dorri Esfahani (Iran-Canada)

Abdolrasoul Dorri Esfahani was a member of Iran’s nuclear deal negotiating team

The accountant was an adviser to the governor of Iran’s central bank and was a member of the Iranian negotiating team for the country’s 2015 nuclear deal with world powers, in charge of financial issues.

He was arrested by the Revolutionary Guards in August 2016 just before he was due to board a flight to Canada, and was accused of “selling the country’s economic details to foreigners”.

In May 2017, a Revolutionary Court in Tehran convicted Dorri Esfahani on espionage charges, including “collaborating with the British secret service”, and sentenced him to five years in prison.

That October an appeals court upheld Dorri Esfahani’s sentence, despite Intelligence Minister Mahmoud Alavi insisting that he was innocent.

Kamran Ghaderi (Iran-Austria)

Kamran Ghaderi’s wife insisted that he was a “simple businessman”

The CEO of Austria-based IT management and consulting company Avanoc was detained during a business trip to Iran in January 2016.

That October, an Iranian prosecutor said Ghaderi had been sentenced to 10 years in prison after being convicted of espionage and co-operating with a hostile state.

His wife insisted that he was a “simple businessman” who was unjustly imprisoned, while human rights groups said he was coerced into confessing to spying.

His conviction was upheld on appeal and his request to the Supreme Court for a retrial has not been granted.

Ghaderi’s physical and mental health has deteriorated in Evin prison. In July 2019, UN human rights experts said he had been denied appropriate medical treatment, despite having a tumour in his leg.

His family and that of another Austrian dual national, Massud Mossaheb, have criticised the Austrian government’s approach to their cases, particularly its failure to publicly request their release.

“After years of continuing to rely on ‘silent diplomacy’, we interpret this either as a sign of resignation, a lack of commitment or a lack of will to consider alternative strategies,” they wrote in an open letter to the foreign ministry in April 2021.

In January 2022, Ghaderi’s wife told the Guardian that it was not clear what Iran wanted in return for his release. “It may not be something directly from Austria, but from the EU,” she said.

Massud Mossaheb (Iran-Austria)

The former businessman, who is an Austrian-Iranian dual national, was arrested in Tehran in January 2019.

Amnesty International cited informed sources as saying Mossaheb was held in a hotel room for three days, where intelligence ministry agents subjected him to torture through sleep deprivation, interrogated him without a lawyer present, and coerced him into signing documents.

He was then transferred to Evin prison, where according to the sources he was tortured.

In April 2020, Mossaheb was sentenced to 22 years in prison after being convicted of “espionage for Germany”, “collaborating with a hostile government” – a reference to Israel – and “receiving illicit funds” from both countries.

Amnesty International said the trial was “grossly unfair”, with the court relying on relying on alleged “confessions” that he retracted in court and told the judge he had made under torture.

In January 2021, a secret audio recording made by Mossaheb in Evin prison was released. In it, he pleaded to listeners to “help me and rescue me from this hell”.

He also said he was suffering from several health issues, including diabetes, neuropathy and a faulty heart valve, and that he needed to have surgery to remove a kidney cyst.

Nahid Taghavi (Iran-Germany)

Nahid Taghavi was an advocate for women’s rights in Iran

The retired architect, a German-Iranian dual national, was arrested at her apartment in Tehran in October 2020 and accused of “endangering security”.

She was placed in solitary confinement at Evin prison and not given access to lawyers, German diplomats or members of her family, according to her daughter Mariam Claren.

Taghavi was repeatedly subjected to coercive questioning without the presence of lawyers, according to Amnesty International. Interrogators reportedly asked her about meeting people to discuss women’s and labour rights, and possessing literature about those issues.

In August 2021, she was convicted by a Revolutionary court in Tehran of “forming a group composed of more than two people with the purpose of disrupting national security” and “spreading propaganda against the system”. She was sentenced to 10 years and eight months in prison.

Taghavi had denied the charges, the first of which was apparently related to a social media account about women’s rights, and Amnesty said the trial was “grossly unfair”.

Ms Claren wrote on Twitter that her mother “did not commit any crime. Unless freedom of speech, freedom of thought are illegal”.

She has said her mother has been denied adequate healthcare by prison and prosecution authorities, despite doctors saying in September 2021 that she needed surgery on her spinal column.

Karan Vafadari and Afarin Neyssari (Iran-US)

Karan Vafadari and Afarin Neyssari were reportedly released on bail in 2018

The couple, who are Zoroastrians, own a well-known art gallery. They were arrested by the Revolutionary Guards at Tehran’s international airport in July 2016.

Two weeks later, the Tehran prosecutor announced that “two Iranian dual nationals” had been charged with hosting parties for foreign diplomats and Iranian associates during which men and women mixed and alcohol was served.

Iran’s constitution says adherents of Zoroastrianism – an ancient, pre-Islamic religion – are not subject to Islamic laws on alcohol and mixed gender gatherings.

In early 2017, further charges were brought against Vafadari and his wife, including “co-operation with enemies of the state”, “activities to overthrow the regime” and “recruitment of spies through foreign embassies”.

In January 2018, Vafadari wrote in a letter from Evin prison saying that a Revolutionary Court had sentenced him to 27 years in jail and his wife to 16 years, according to the US-based Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI). He vigorously rejected all the charges they faced.

The couple’s sentences were later reduced to 15 years and 10 years respectively, their son said.

In July 2018, the authorities reportedly released them on bail, pending an appeal.

[ad_2]

Source link