[ad_1]

The names of successful black South African cricketers trip off the tongue these days – Kagiso Rababa, Temba Bavuma, Lungi Ndidi to name just three.

However, South Africa’s first tour post-Apartheid isolation might not have happened were it not for two little-known black cricketers plucked from obscurity, never to bowl or face a single delivery in international cricket.

Hussein Manack and Faiek Davids were part of the first South Africa team to tour India, 30 years ago this month, and their story is one of intrigue and what might have been.

That’s because when South Africa first named their tour party for three one-day internationals in India, it needed a political intervention to ensure the squad wasn’t all white.

“I got a phone call from the president of Indian cricket,” Dr Ali Bacher, then the chief executive of the newly established United Cricket Board of South Africa, told BBC Sport. “He said ‘Ali it’s great you are coming, but an all-white team will become a huge problem in India’. I said leave it with me. I will sort it.”

And sort it, Bacher did.

In the days before mobile phones, Manack remembers getting a call one evening at his home near Johannesburg.

“Dr Bacher asked if I would like to come to India in a non-playing capacity to gain experience,” Manack recalls.

In Cape Town, Davids received the same invitation: “I didn’t expect something like this at all. I didn’t even have a passport.”

Both players accepted the offer but had questions in their minds as to why they had been included.

“I discussed it with people close to me. It was going to be a groundbreaking tour for South Africa. But there was a feeling it was a window-dressing exercise,” recalls Manack.

Davids adds: “I was surprised to be earmarked as a developmental player at 28 years old. I wasn’t comfortable with it.”

Two young white players were also selected in the development quartet – the future South Africa captain Hansie Cronje and spinner Derek Crookes, who would go on to play 32 one-day internationals.

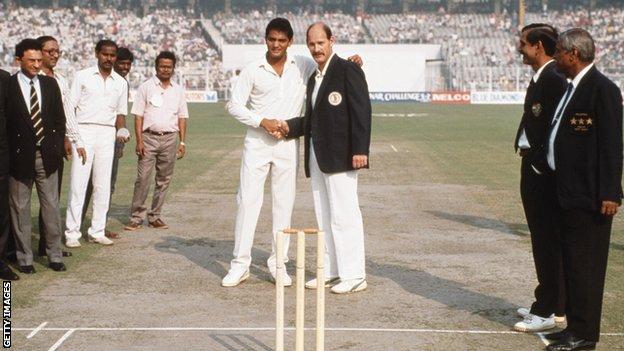

The reception the squad received in Kolkata – Calcutta as it was then – surpassed all expectations.

“On the journey from the airport to the hotel there were 100,000 people lining the streets to welcome us. It was unbelievable,” said Bacher.

The 10-day tour included three one-day matches, as well as a meeting with Mother Theresa and a visit to the Taj Mahal.

“The players were very welcoming and friendly. But I felt very of out of place and I thought we [himself and Davids] were there as a token to show to the Indian media,” remembers Manack.

Davids felt the same isolation but was keen to gain as much experience as possible: “Being aware you were never going to play was very difficult, but I thought I am here, and it was good to be involved with the team to try and be part of it in future. ”

The pair watched South Africa’s first official international for 21 years from the sidelines.

“It was a very enlightening experience to meet players like Tendulkar and Sanjay Manjrekar,” Manack said. “When we got to Eden Gardens for the first match, I remember [Tendulkar] clearing the mid-wicket boundary.

“He played with so much confidence in front of 100,000 people it was unbelievable”.

But there was no international recognition for Manack or Davids in the years that followed. So, what did happen when they returned home to a unified domestic game?

“I played among some amazing black cricketers that would easily have made any South African side,” said Manack. “But they were not given the recognition they deserved. They were always in the shadows.”

Davids found as a black player you had to “prove yourself over and over again”, adding: “It wasn’t what I thought it would be. The history books will tell you the opportunities Hansie Cronje and Derek Crookes got were very different to what myself and Hussein got. Those years were tough times.”

That disillusionment led to many black players giving up the game.

“Within two years many had just retired and stopped playing cricket,” Manack recalls. “Suddenly we were not seen as good enough. So many cricketers said we are just wasting our time here. It’s a joke. ”

The progress towards a multi-racial South African team in the past 20 years came too late for Manack and Davids, and players of their generation. After short first-class careers with Transvaal and Western Province respectively, both men remain in the sport today.

Manack was a national selector for seven years and is now a respected commentator with the South African Broadcasting Corporation. Davids, who went to the 1992 World Cup also as a non-playing member, is now coaching with his former side in Cape Town.

And of the India tour 30 years ago this month?

“I have no regrets,” said Davids. “My only regret is I would have love to have played in front of hundreds of thousands of people ”

From Segregation to Integration: The Story of South Africa’s Return to International Cricket is available now as a podcast.

[ad_2]

Source link