[ad_1]

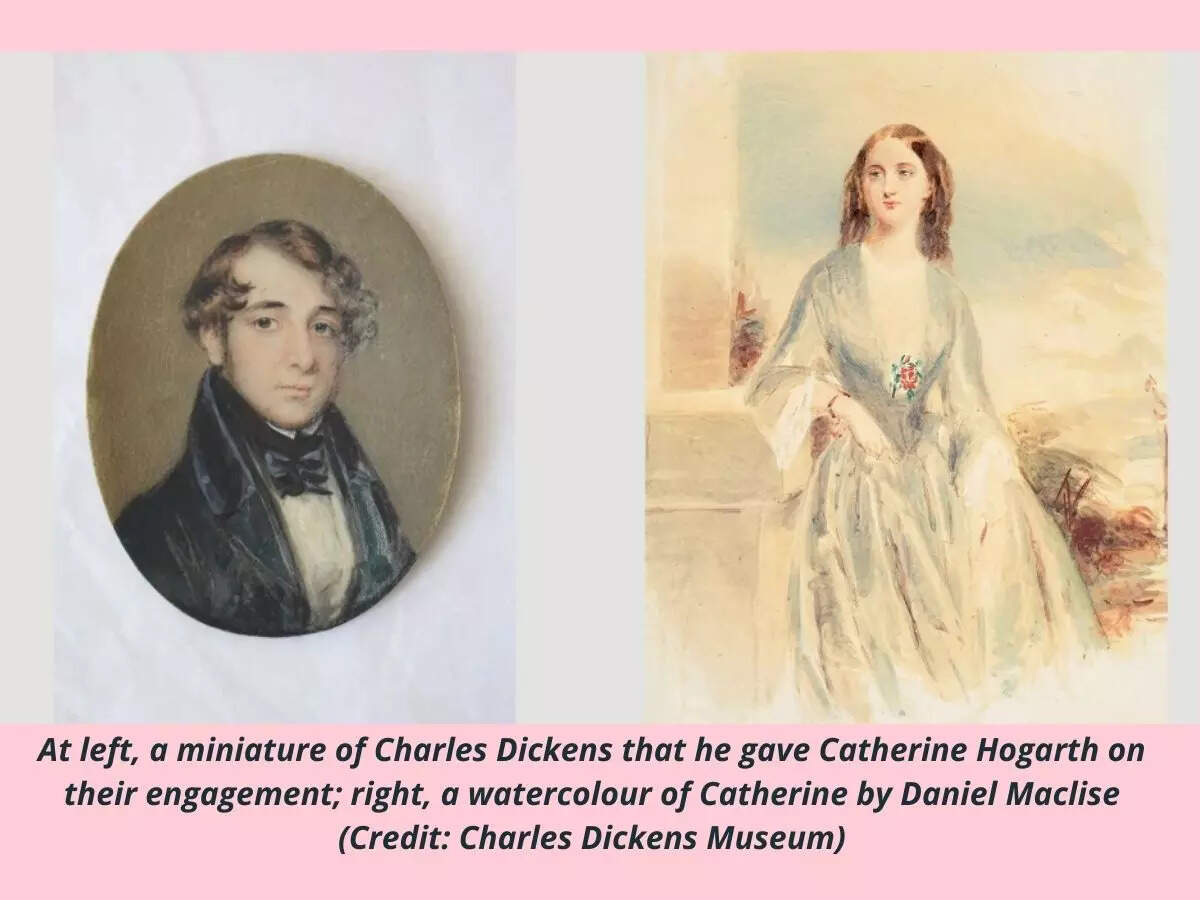

Catherine was the wife of Charles, the mother of his ten children, and a writer of domestic management. Her father was a journalist for the Edinburgh Courant, and later became a writer and music critic for the Morning Chronicle, where Charles was a young journalist. Charles immediately took a liking to the attractive 19-year-old Catherine and invited her to his 23rd birthday party.

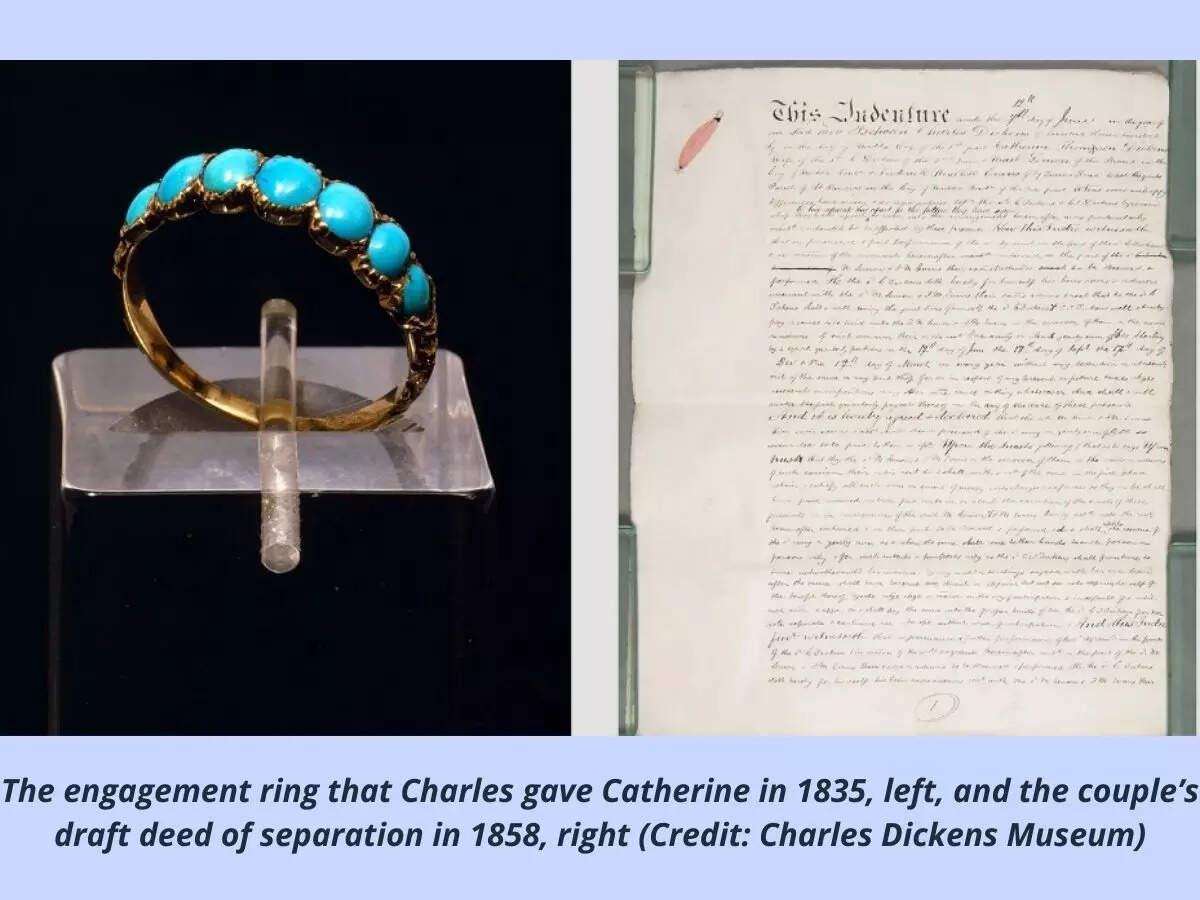

Catherine and Charles later became engaged in 1835 and were married on 2 April 1836 in St Luke’s Church, Chelsea. They set up a home in Bloomsbury and went on to have ten children. During that period, Charles wrote that even if he were to become rich and famous, he would never be as happy as he was in that small flat with Catherine.

However, over the years, Charles found Catherine an incompetent mother and housekeeper and blamed her for the birth of their 10 children, which caused him financial worries. He claimed that her coming from a large family had caused so many children to be born. He even tried to have her diagnosed as mentally ill in order to commit her to an insane asylum. If this wasn’t enough, to ensure no more children could be born, he ordered their beds to be separated and put a bookshelf in between them.

The couple’s separation in May 1858, after Catherine accidentally received a bracelet meant for English actress Ellen Ternan, was much publicized, and rumors of Charles’ affairs were numerous.

According to writer Gladys Storey, her friend, i.e. Charles’ third daughter Kate, told her that she had seen her mother cry and that once a bracelet destined for Ternan had been sent to the house by mistake, and Catherine had accused Charles of having a love affair with her.

Charles denied all accusations of adultery, alleging that he always sent gifts to his favorite actors and actresses. He used these accusations as another reason why he couldn’t continue to live under the same roof as his wife. On 12 June 1858, he published an article in his journal, Household Words, denying rumors about the separation:

“Some domestic trouble of mine, of long-standing, on which I will make no further remark than that it claims to be respected, as being of a sacredly private nature, has lately been brought to an arrangement, which involves no anger or ill-will of any kind, and the whole origin, progress, and surrounding circumstances of which have been, throughout, within the knowledge of my children. It is amicably composed, and its details have now to be forgotten by those concerned in it … By some means, arising out of wickedness, or out of folly, or out of inconceivable wild chance, or out of all three, this trouble has been the occasion of misrepresentations, mostly grossly false, most monstrous, and most cruel – involving, not only me, but innocent persons dear to my heart … I most solemnly declare, then – and this I do both in my own name and in my wife’s name – that all the lately whispered rumours touching the trouble, at which I have glanced, are abominably false. And whosoever repeats one of them after this denial, will lie as wilfully and as foully as it is possible for any false witness to lie, before heaven and earth.”

Charles also wrote a letter that made its way into the New York Tribune, in which he said that the “peculiarity of her character” had “thrown all the children” onto the care of Catherine’s sister Georgina, the Dickens family housekeeper.

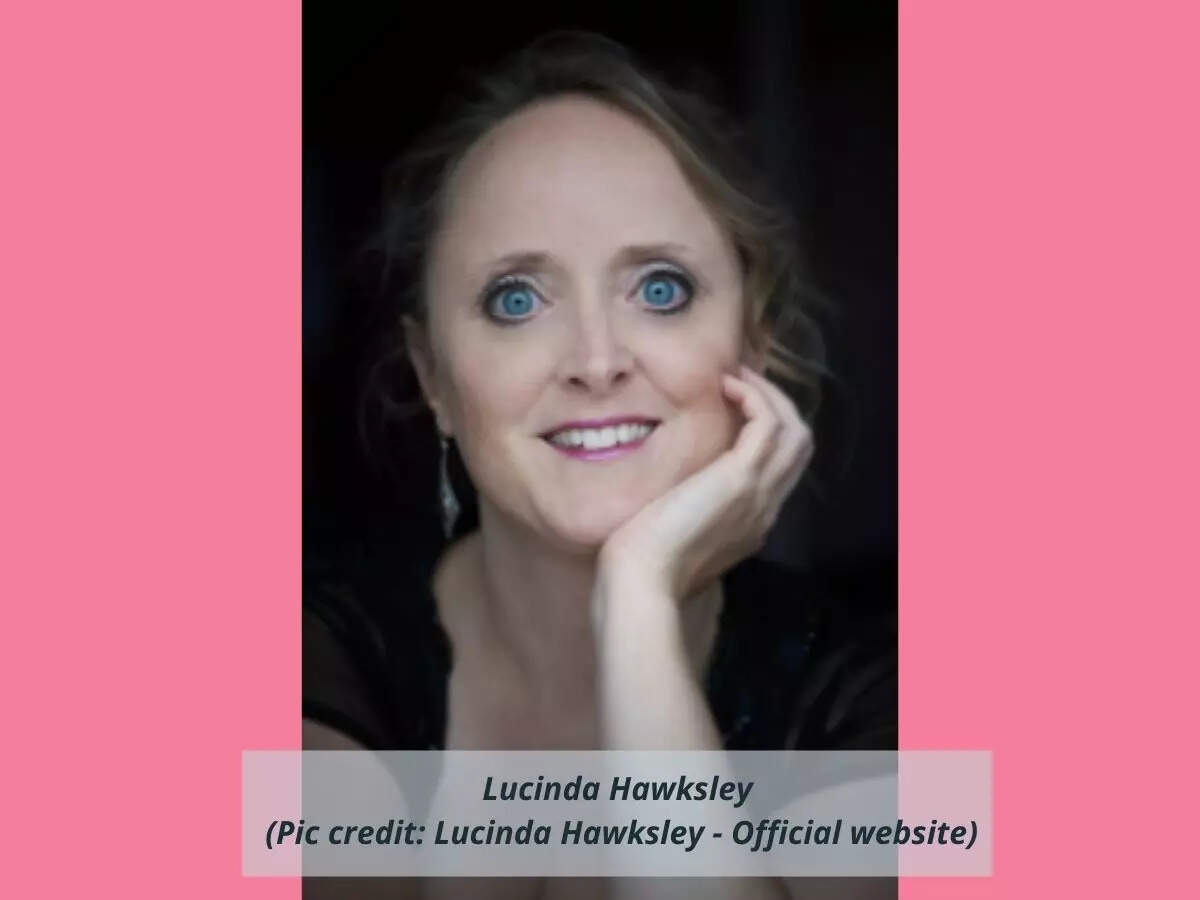

Fast forward to 2016, Lucinda Hawksley, Charles and Catherine’s great-great-great-granddaughter wrote an article for the BBC.

“In addition to being a mother, Catherine was an author, a very talented actress, an excellent cook and, in her husband’s words, a superb travelling companion. But as the wife of such a famous figure, all of that has been eclipsed,” she wrote.

“When the couple met, Charles put Catherine on a pedestal. His childhood was scarred by poverty and the shadow of the debtors’ prison; in contrast, Catherine came from a comfortable, happy middle-class family. I believe Dickens wanted to emulate that: he wanted a wife and mother who would give his children stability and a carefree home. Catherine became his ideal woman,” she added.

Explaining how Charles’ success affected Catherine, Lucinda mentioned that the latter began to be overlooked. Her multiple pregnancies took a toll on her health, energy, and their marriage.

“But the real story of Catherine is that of a fun-loving young woman who, as the wife of an international celebrity, travelled widely and had the opportunity to see and experience things that most women of her era and social status did not. She and Charles were very keen amateur actors, for example. Catherine not only performed in shows at home, but on stage in both the United States and Canada,” Lucinda explained.

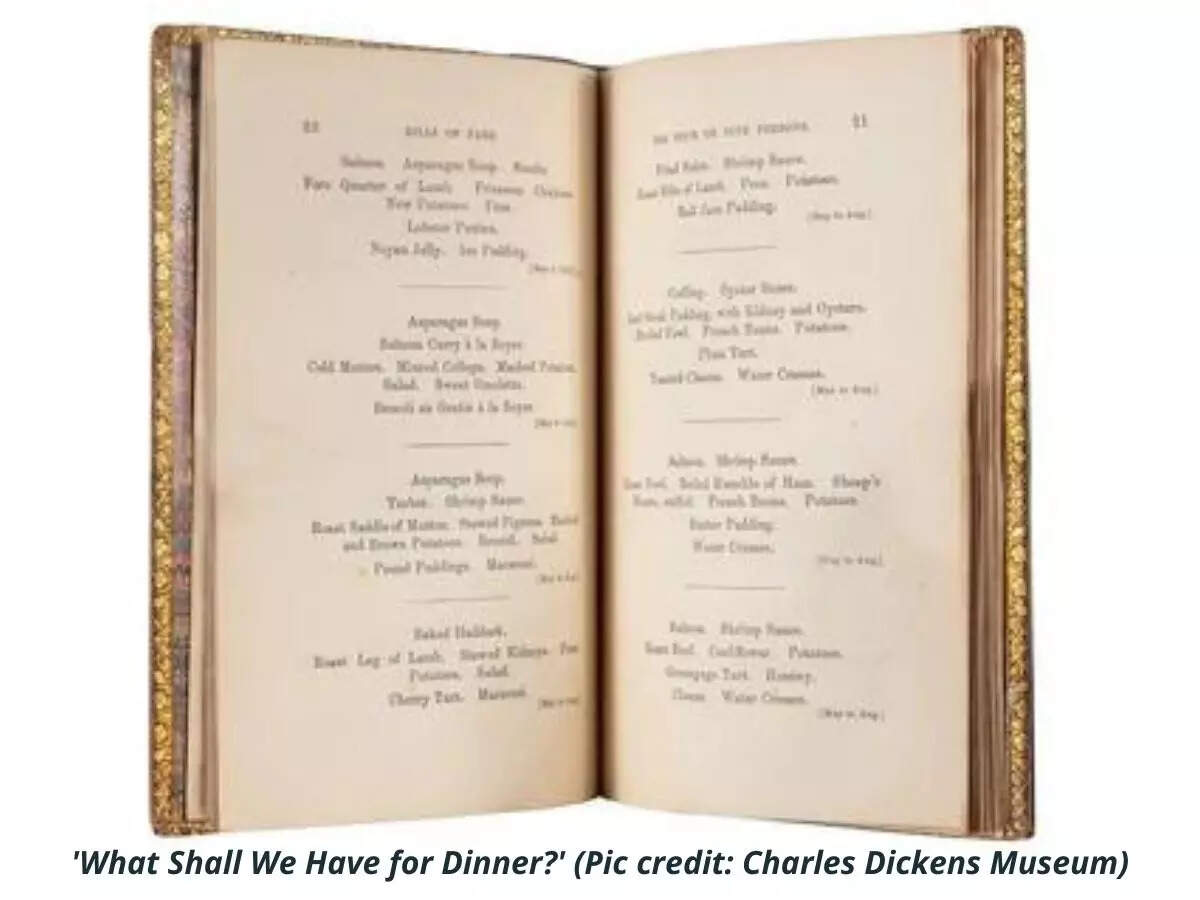

“Another of Catherine’s achievements? Publishing a book. When I researched it, I was infuriated to discover how many people – even respected academics – have claimed that it was written by Charles,” she added.

For the unversed, Catherine’s book is titled ‘What Shall We Have for Dinner?’. It’s a guide for young wives, which advises them on household tasks and cooking dishes for anywhere from 2 to 18 people. However, interestingly, later critics dismissed Catherine’s recipes as bad food from an unstable fat woman.

Furthermore, Professor of English Lillian Nayder, in her 2010 biography of Catherine, explained this perception:

“The book mostly offers meal plans or bills of fare, and Dickens biographers have used it against her, as more evidence of why the marriage “didn’t work out.” Her husband was seen as light and mercurial, and she was seen as this burdensome body weighing him down with macaroni and cheese.”

Furthermore, talking about Catherine’s body type, which has also been a subject of ridicule for later critics, Nayder wrote, “Most of the negative interpretations of her body reflect the way her marital history has been reinvented by critics, following Dickens’ lead. The criticism of how she looked wouldn’t have been launched had the marriage remained intact.”

It is clear that Catherine’s side of the split has remained obscured from history. This changed in 2014 when University of York professor John Bowen came to know about the existence of 98 previously unknown letters that show Charles was actually gaslighting Catherine. Sometime in 2019, Bowen sorted through these letters himself at the Harvard Theatre Collection in Cambridge, where they ended up.

The letters were written by Dickens’ family friend and neighbor Edward Dutton Cook to a fellow journalist, and they include details about the couple’s separation, which Catherine shared with Cook in 1879, the year she died.

In them, Cook recounts: “He [Charles] discovered at last that she had outgrown his liking…He even tried to shut her up in a lunatic asylum, poor thing!”

In fact, researchers were previously aware of an account by Catherine’s aunt, Helen Thomson, that stated Charles had tried to coax her niece’s doctor into diagnosing her as mentally unsound.

This comes as a shock for Charles’ aficionados who remember him as an advocate for social reform because of his sympathetic depictions of the plights of Britain’s poor and exploited and for establishing a safe house for homeless young women. He also visited insane asylums and wrote appreciatively about the more humane treatment patients were receiving, in contrast to the “chamber of horrors” such facilities had historically been.

Finally, after all this, if Catherine ever had the chance to confront Charles, she might have used these lines from his own last novel, ‘Our Mutual Friend’:

“You could draw me to fire, you could draw me to water, you could draw me to the gallows, you could draw me to any death, you could draw me to anything I have most avoided, you could draw me to any exposure and disgrace. This and the confusion of my thoughts, so that I am fit for nothing, is what I mean by your being the ruin of me.”

Pic credit: Charles Dickens Museum/Official website

[ad_2]

Source link